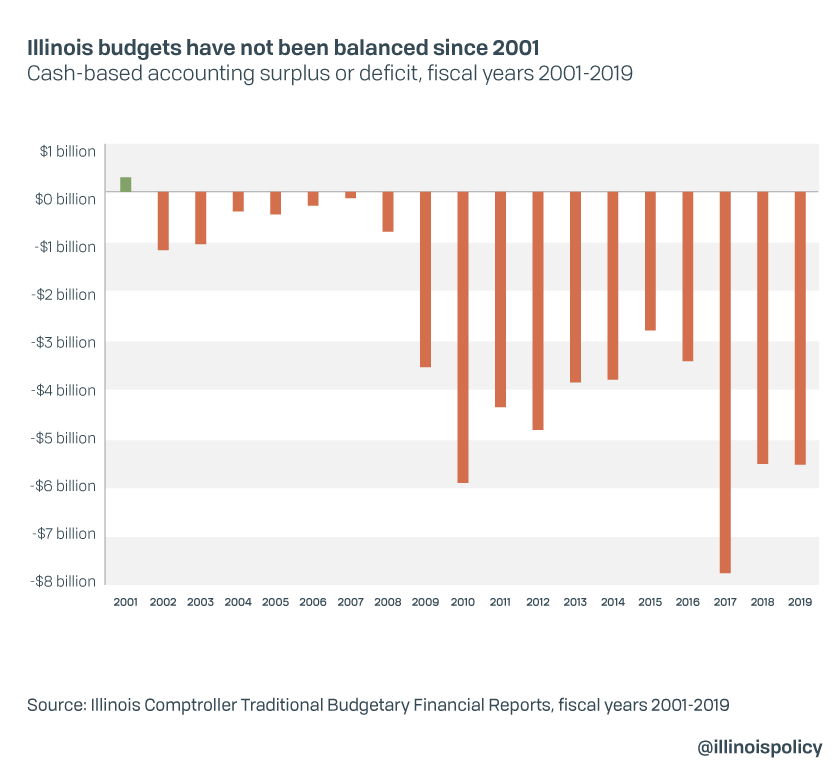

The years 2010 through 2019 will go down in Illinois history as a decade of public policy failure and economic decline. High fixed costs for pensions and government worker health care have prevented the state from balancing its budget in any year since 2001. Since the Great Recession in 2008, the state’s fiscal imbalance has grown progressively worse. Illinois now holds the lowest credit rating in the nation and is drowning in high-interest debt as a result.

To date, policymakers have responded with one main strategy intended to reverse this long-running fiscal decline: tax hikes. Attempts to bring in more revenue through higher income taxes, and more recently, tax increases on a variety of consumer goods, have failed to improve state finances. Meanwhile, these tax increases have driven Illinois’ total state and local tax burden to one of the highest in the nation.

High tax burdens have harmed private sector business investment, jobs growth and overall economic activity. Lower taxes and better job opportunities in other states are the core drivers of the Illinois exodus, resulting in a net population loss of 168,700 residents from 2010-2019. This has significantly eroded the tax base and is a large contributing factor to poor economic growth compared with other states.

Though some elected officials and interest groups continue to cast doubt on the fact that high taxes drive residents to other states, the relationship is confirmed both by Illinois public opinion data and peer-reviewed economics literature.

The state’s fiscal crisis has been built during nearly two decades of spending more than it brings in, driven primarily by unsustainable and rising costs for public sector pensions. As a result, Illinois’ overall financial health is perhaps the worst in the nation.

To reverse these worrying trends, policymakers must be willing to entertain new and transformative ideas, not simply double down on variations of the same failed strategy of the past decade.

On Nov. 3, 2020, residents will have an opportunity to judge the worthiness of one plan to deal with these problems: more revenue from a $3.7 billion progressive income tax hike, which Gov. J.B. Pritzker has called the “fair tax.” The governor’s budget office in 2019 presented this plan in an official state document as the only alternative to “draconian” cuts in core government services.

This is a false choice.

The progressive income tax amendment would open the door to higher taxes on all Illinois residents and increase uncertainty about future tax rates for both businesses and residents. It would also mean moving in the opposite direction of national trends and of other states in the region.

By pursuing reforms that address the root cause of Illinois’ crisis, Illinois can solve its fiscal problems and protect core services without resorting to a constitutional amendment that grants extreme, new taxing powers to Springfield.

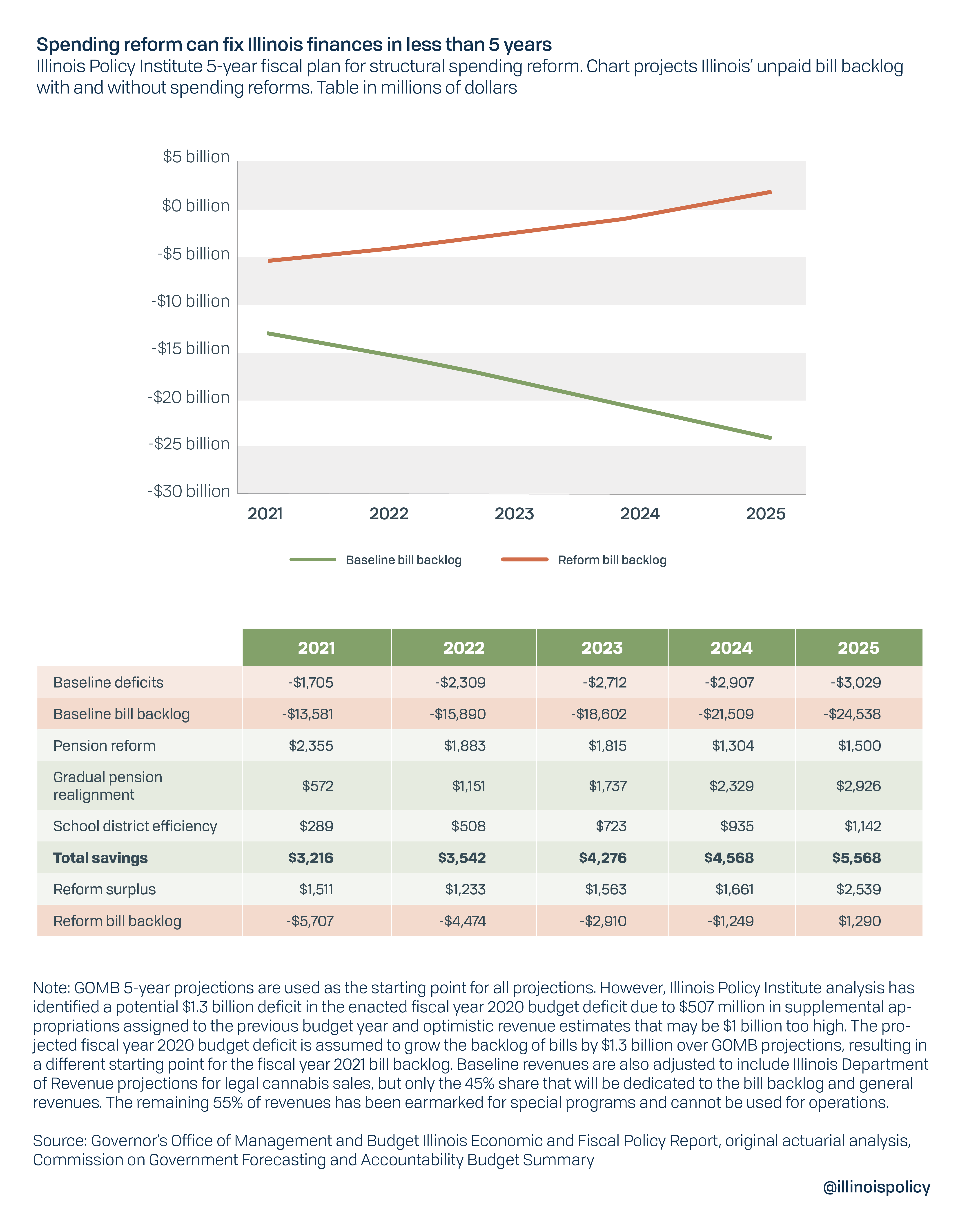

Three commonsense ideas can enable Illinois to immediately balance its budget, pay down debt and cut taxes during the course of five years.

1. Amend the state constitution so the growth in future, not-yet-earned pension benefits can be reduced to a level that is sustainable and affordable.

- First-year savings: $2.4 billion

- Five-year savings: $8.9 billion

2. Align responsibility for paying new pension benefits with accountability for negotiating compensation for school and university employees.

- First-year savings: $571 million

- Five-year savings: $8.7 billion

3. Invest in K-12 education by reducing administrative bloat in school districts, rather than pouring $350 million more annually into an inefficient system.

- First-year savings: $289 million

- Five-year savings: $3.6 billion

Each of these reforms has received bipartisan support in Springfield within the past decade. A fiscal plan that embraces them can immediately balance the state budget, eliminate short-term debt and create surpluses that can be used to both shore up the state’s rainy-day fund and provide tax relief within five years.

If leaders pursue meaningful structural spending reforms, Illinois can strengthen its economy, guard against fiscal calamity and reverse negative population trends.

Many have already given up on Illinois. Six consecutive years of population loss, driven by high taxes and a weak economy, show residents are voting with their feet.

But hope is not lost. Illinois’ financial problems are huge, but not insurmountable. To dig our way out, elected leaders must simply show the courage and the will to adopt transformative changes to how state government spends taxpayer money.

Introduction: Illinois’ budgeting history demands a new path forward

Illinois’ financial health is nearly at the bottom of the nation’s states. The last time the state had a balanced budget was fiscal year 2001.1 As a consequence of nearly two decades of spending more than it brings in, Illinois built up massive debt burdens that endanger residents’ future prosperity.

Tax hikes have not solved this problem. And tax hikes cannot solve it going forward. Illinois needs structural spending reform of its largest cost drivers to ensure state government spending grows at a pace residents can afford. This is the only sustainable way for the state to balance its budget, pay down debt and give tax relief to residents. The state should also enact statutory or constitutional fiscal constraints – including a spending cap and true balanced budget requirement – to ensure Springfield does not revert to its historical overspending in the future.

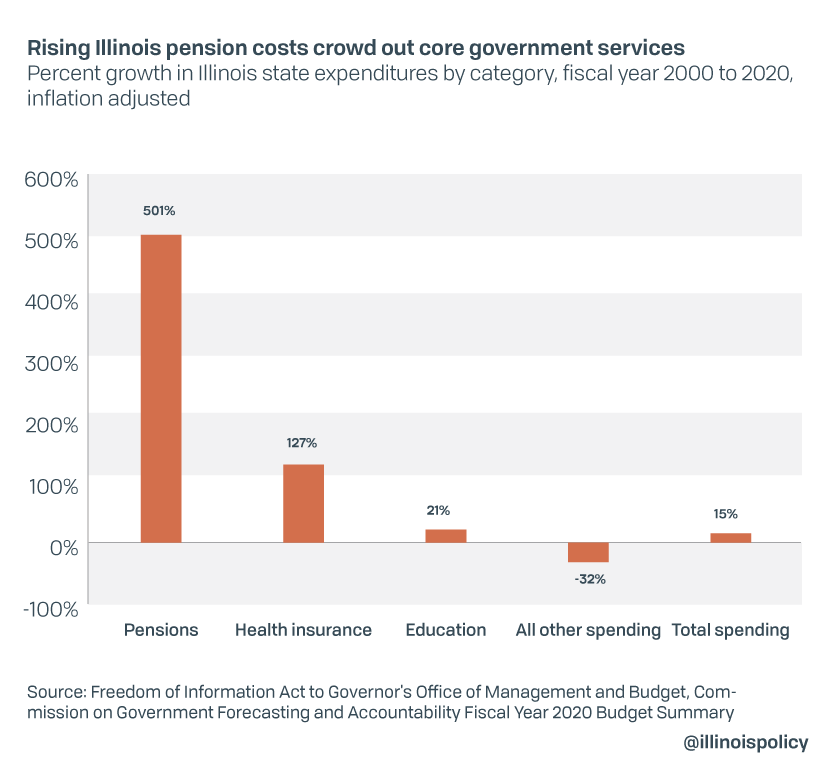

Data clearly show the state’s biggest fiscal challenge is its broken pension system.

Since fiscal year 2000, after adjusting for inflation, state spending on pensions has grown 501%. Spending on government worker health insurance has grown 127%. Meanwhile, spending on K-12 education is up 21%. All other spending – including social services for the disadvantaged, higher education and public safety, among other items – is down by 32% in real terms. Total real spending has risen by 15% during those 20 years.

This rapid growth in the cost of pensions not only crowds out investment in valuable government services, but also drives the state’s high tax burdens. Furthermore, these data show that while Illinois’ fiscal crisis is caused by overspending, policymakers are actually reducing investment in programs residents often want in order to give public sector workers health care and pension benefits that residents can’t afford.

Unfortunately, the state in 2019 agreed to a contract with its largest public sector union, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, which preserved extremely generous health care benefits at little cost to employees. This means meaningful reform to the state employee group health insurance plans cannot be enacted until the current contract expires on June 30, 2023. Combined with generous automatic raises, backpay for raises not given under the previous administration and $2,500 bonuses, the contract will cost at least $3.6 billion more than a taxpayer-friendly contract proposed by the Illinois Policy Institute.2

Research by economists and financial professionals demonstrates just how bad the fiscal crisis has become in the Land of Lincoln compared to other states. For example:

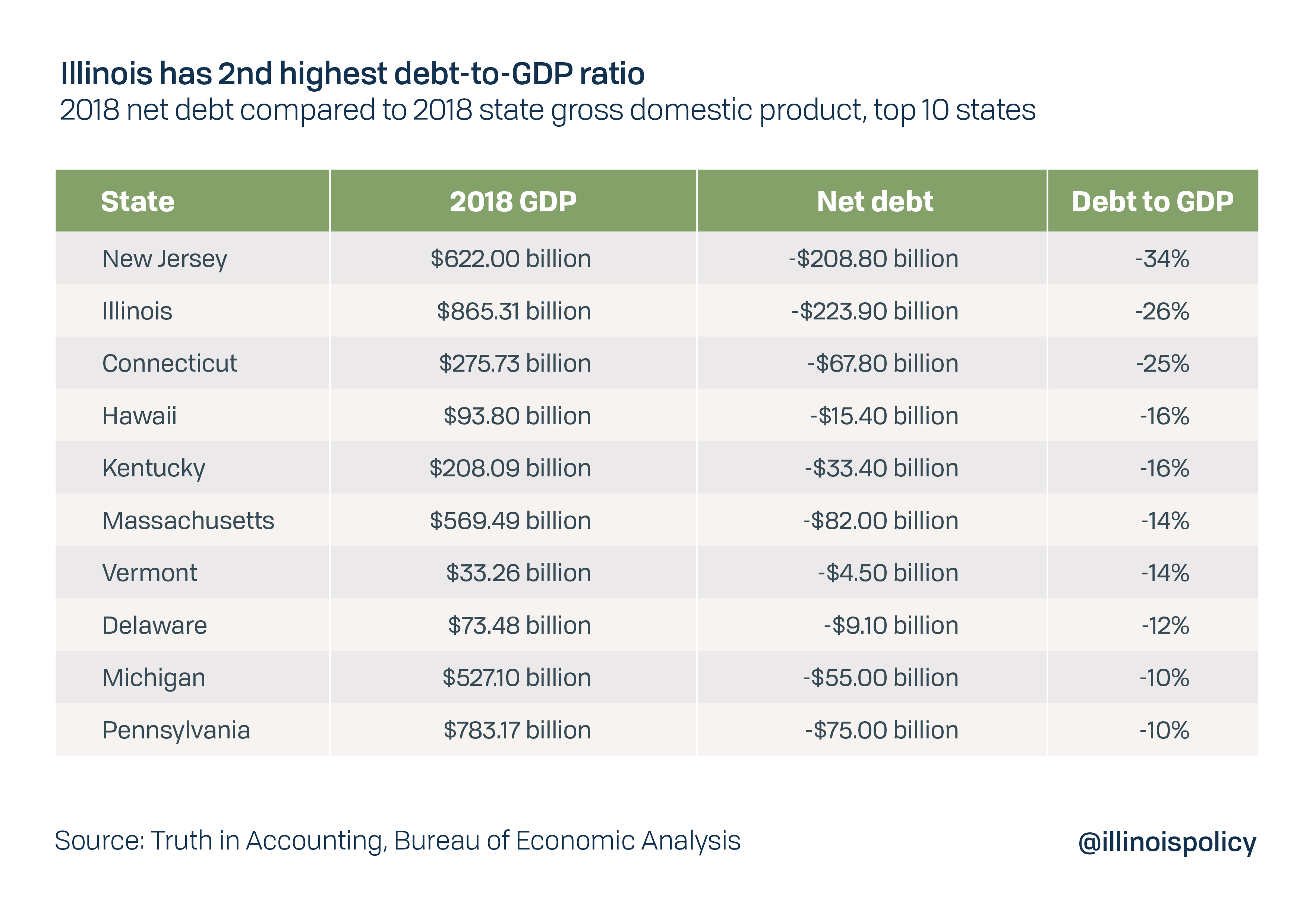

- Taxpayers in the Prairie State face the second-highest debt burden per taxpayer at $52,600 each, second only to New Jersey taxpayers’ $65,100, according to fiscal watchdog Truth in Accounting.3 Illinois has a net debt of $223.9 billion, mostly for pensions and retiree health care.4

- A recent study from George Mason University ranked Illinois the lowest of all 50 states in overall fiscal health, a measure that considers a government’s ability to pay short- and long-term bills, weather recessions with rainy-day savings, and its ability to raise taxes without harming the economy.5

- A report this year from credit ratings agency Moody’s Investors Service found that Illinois was one of two states least prepared for the next recession, the other being New Jersey. The stress test considers how volatile existing revenues are – meaning how much they decline during an economic downturn – as well as rainy-day fund reserves and the risk posed by pension debt, a threat faced by many U.S. governments.

One comprehensive and high-level way to measure financial health is to compare a state’s total net debt – all the bills it owes minus the assets on hand available to pay them – with the size of a state’s economic output, or gross domestic product. By this measure of “ability to pay,” which is similar to the debt-to-income ratio a bank looks at when considering a personal finance loan, Illinois ranks second-worst after New Jersey.

Notably, political leaders in New Jersey have started a push to fix state finances with structural spending reform. New Jersey Senate President Stephen Sweeney, a Democrat and private-sector union official, has been pushing for significant changes to government worker health care and pension systems.6

The same cannot be said in Illinois, where leaders have taken no steps to structurally reform the state’s largest cost drivers since 2015, when the Illinois Supreme Court blocked an earlier attempt at pension reform.

In recent years, one policy response has dominated all others in the face of Illinois’ deteriorating fiscal condition: higher taxes. This strategy has failed to fix the state’s financial challenges, which are at root a spending problem. They have succeeded in contributing to consistent population loss and lagging economic growth.

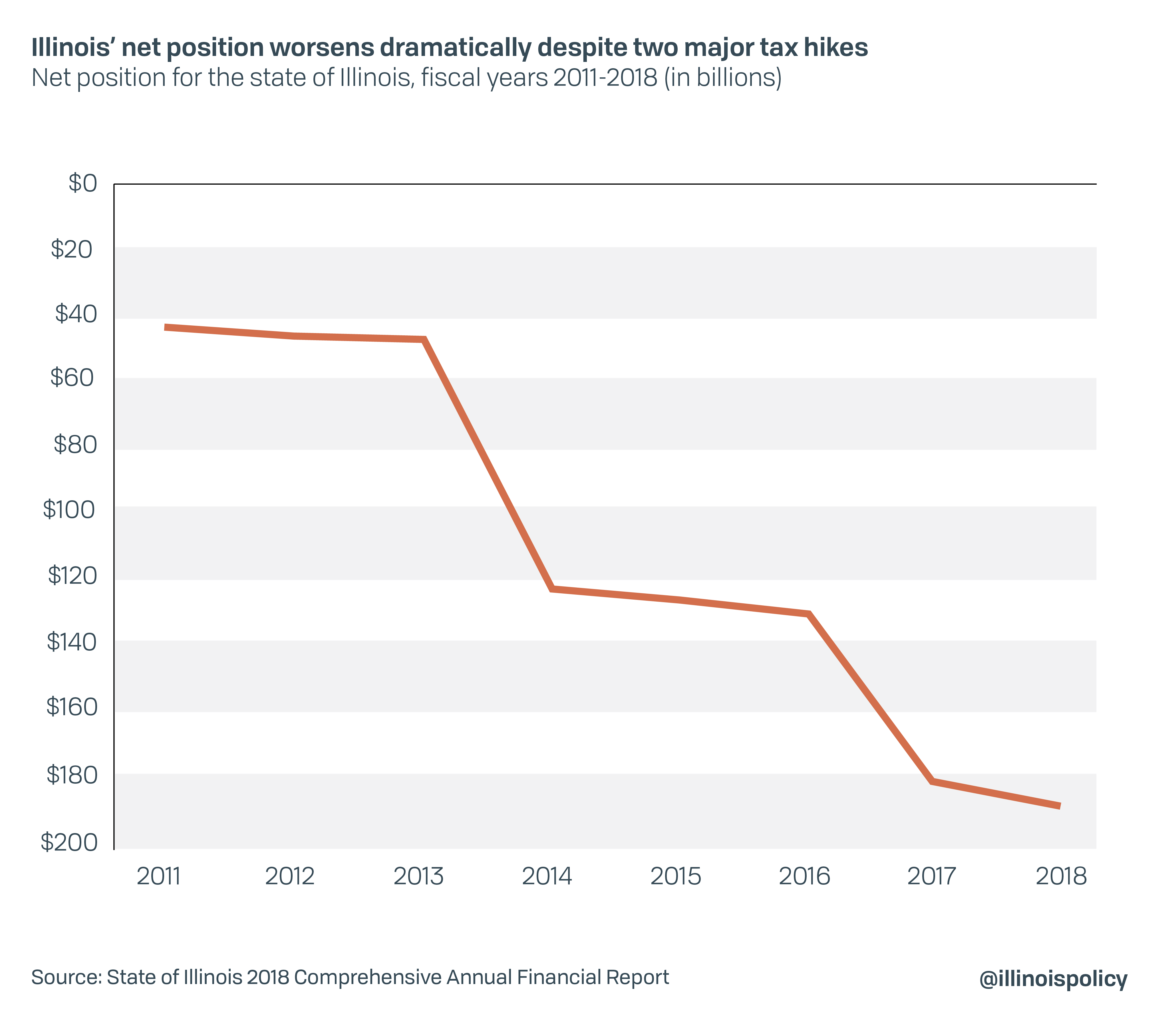

Since Illinois first attempted to solve its problems with a “temporary” income tax hike in 2011, the negative net position of the state – which is similar to an individual’s net worth – has worsened by a factor of four to $189.1 billion from $43.6 billion.7 This happened in the midst of a record-long economic expansion. Note that these figures are slightly smaller than the net debt figure used above for the GDP ranking, because the standard net position reported in official statements includes some assets that cannot be sold to pay bills, such as those restricted by law or contract.

Meanwhile, residents are signaling their displeasure by leaving the state. During the past six years, Illinois lost population each year for a net loss of 223,308 people.8 The most common reason residents give for wanting to leave is the high tax burden, according to public opinion polling conducted for NPR and the University of Illinois-Springfield.9 Additionally, expert economics literature has consistently found that Americans move to avoid high total state and local taxes, and high income and property taxes in particular.10 Relative total tax burdens have even more impact on migration decisions than differences in specific tax rates, such as sales or income taxes.11

The commonsense takeaway for policymakers is that while differences in tax structures do matter, residents and businesses care more about how much of their income the government takes than they do about how it is taken. Nationwide data show a migration trend to low-tax states from high-tax states, and this trend is likely to accelerate now that the federal government has placed a $10,000 limit on the state and local tax deduction, which essentially reduced a subsidy to high-tax states.12

Illinois’ high tax burden also hurts private-sector investment, a one-two economic punch when combined with Illinois’ people problem.

Illinois Policy Institute analysis found the 2011 state income tax hike cost the state economy $55.8 billion in gross domestic product, along with 9,300 jobs over four years.13 This points to the fundamental problem with trying to solve deficits with tax hikes in a state that already has such high tax burdens: any further increase harms the state’s tax base and economy, which fund government services. Past a certain point, raising new revenue becomes a self-defeating strategy by pushing out the very businesses and residents that government relies on to solve financial problems.

Illinois is well past the point of diminishing returns, with personal finance website Kiplinger recently ranking Illinois the “least-friendly” state in the nation for taxpayers.14 This is consistent with rankings from other independent groups that have placed Illinois at or near the highest total state and local tax burden in the country in recent years.15

Despite the failure of the first tax hike and the economic harm it caused, lawmakers broke their promise to let the higher rate expire and raised personal income taxes again in 2017, now set at a permanent 4.95%. Again, this strategy failed, with the state failing to balance its budget in any of the subsequent years despite record revenues. Pritzker’s first budget has an estimated deficit as high as $1.3 billion,16 even though the state added 20 new or higher taxes and fees that will bring in $4.6 billion more per year to fund the state budget and a new capital plan.17

Against this backdrop, the General Assembly placed a constitutional amendment on the ballot to eliminate Illinois’ flat tax protection and allow for the adoption of a progressive income tax. Lawmakers sent the measure to voters and on Nov. 3, 2020, Illinoisans will decide whether to approve Pritzker’s plan to raise $3.7 billion in higher income taxes and give lawmakers greater taxing authority.18

Voters will either allow Springfield to double down on failure or send a strong message that it is time for a new path.

Pritzker has repeatedly said his progressive income tax plan – which he calls the “fair tax” – is the only way to turn the state around. His official government budget report stated the only alternative to higher taxes is “draconian cuts to services,” with 6.5% across-the-board cuts in agency operations.19 Former Gov. Pat Quinn presented voters with a similar false choice in 2014, claiming severe cuts to core services were the only alternative to his planned income tax increase.20

Adoption of a progressive income tax would take Illinois in the opposite direction of both national tax trends and trends in neighboring states, with which Illinois competes for businesses and residents. In 2019 alone, five states cut corporate income tax rates and six cut personal income tax rates.21

A much better alternative is to structurally reform the largest cost drivers to bring the budget into balance. This does not require cutting any valuable programs or current services and can be accomplished with ideas that have received bipartisan support in Illinois during the past decade, but upon which lawmakers have yet to act.

Three commonsense ideas can enable Illinois to balance its budget, pay down taxes and cut taxes after just five years.

1. Amend the state constitution so the growth in future, not-yet-earned pension benefits can be reduced to a level that is sustainable and affordable.

- First-year savings: $2.4 billion

- Five-year savings: $8.9 billion

2. Align responsibility for paying new pension benefits with accountability for negotiating compensation for school and university employees.

- First-year savings: $571 million

- Five-year savings: $8.7 billion

3. Invest in K-12 education by reducing administrative bloat in school districts, rather than pouring $350 million more annually into an inefficient system.

- First-year savings: $289 million

- Five-year savings: $3.6 billion

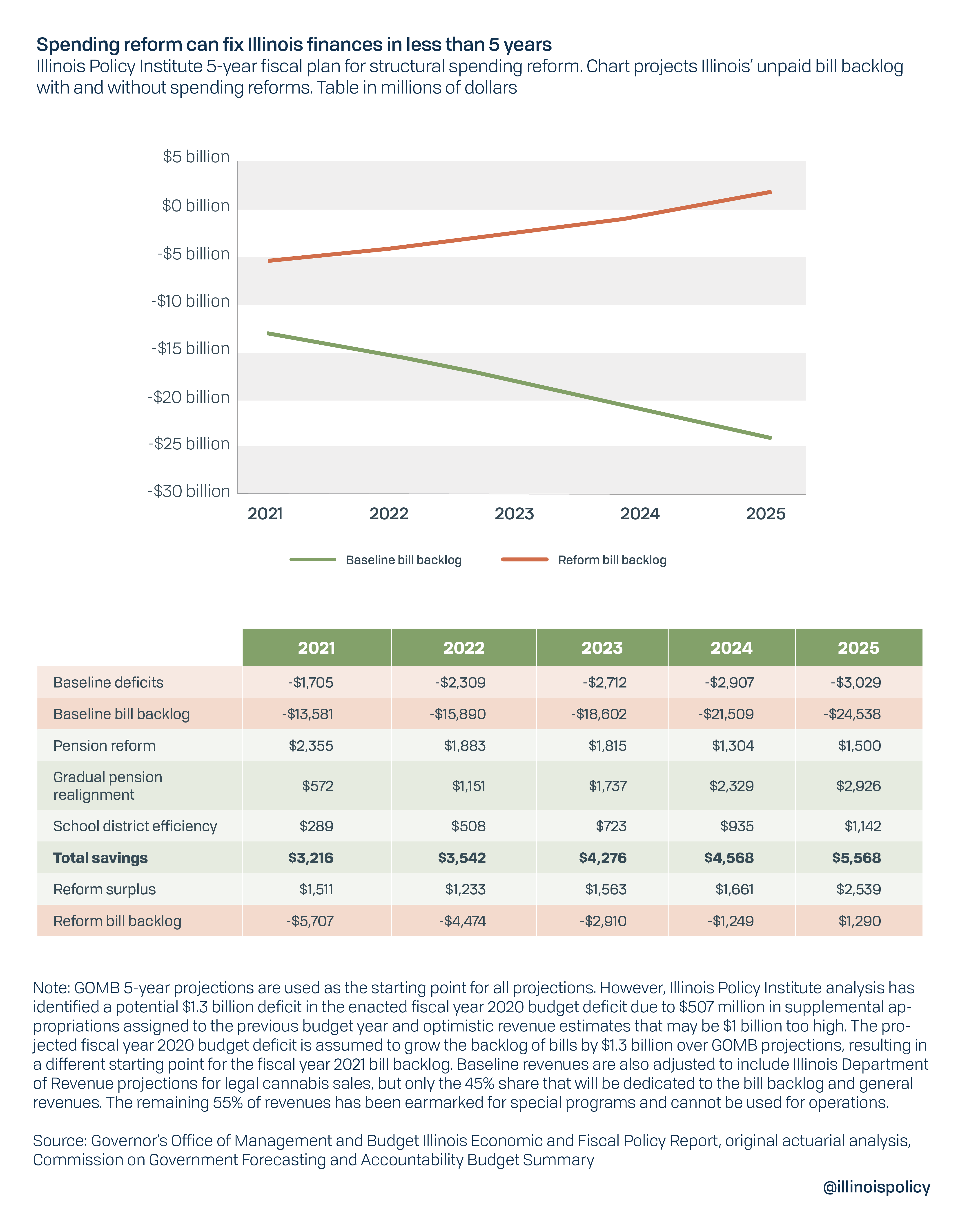

Under official projections from the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, or GOMB, Illinois is projected to end fiscal year 2025 with a $19.2 billion bill backlog, a form of short-term debt that carries high interest penalties. If those optimistic projections of a balanced fiscal year 2020 budget prove false, as such projections have for 19 years running, that backlog could grow faster and larger, reaching $24.5 billion in fiscal year 2025.

If the General Assembly instead adopts the three commonsense structural reforms detailed in this report, the state would end fiscal year 2025 with a nearly $1.3 billion surplus. That surplus should be used first for a large deposit into the state’s rainy-day fund, to ensure Illinois can weather the next recession, and be followed in the subsequent year with tax relief.

Illinois’ financial problems are not insurmountable. They simply require lawmakers to have the will to tackle them properly, by abandoning their tax hike strategy and pursuing structural spending reform.

Ending the pension crisis with reasonable, balanced reform

Illinois’ pension crisis is the worst in the nation and the most severe problem facing the state. Reducing the cost of pensions to a sustainable and affordable level, while still fully funding the system to avoid debt, is the most important task for any Illinois fiscal plan.

According to the latest official projections from the state, unfunded liabilities in the five state pension systems reached $136.8 billion on July 1, 2019.22 The state has only about 40 cents of assets saved for every dollar that would be owed to retirees if benefits continue to grow at levels set under current law.

Local governments in the Prairie State have their own pension problems, adding another $62.71 billion in debt as follows:

- $41.8 billion from Chicago-related pension funds.23 According to data from The Pew Charitable Trusts, that means the city of Chicago alone has more pension debt than 44 U.S. states.24

- $6.9 billion between the Cook County Employees Fund and Cook County Forest Preserve Fund.25

- Nearly $3 billion from the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund.26

- More than $11 billion from the 641 downstate police and fire pension funds.27

Even by official projections, which show lower debt than some outside analysts such as Moody’s have calculated,28 that puts total Illinois state and local pension debt at nearly $200 billion. Clearly, pensions are a problem for taxpayers at every level of government in Illinois.

Financial pressure from pensions on local governments is the leading cause of Illinois’ second-highest-in-the-nation property taxes.29 Reforming pensions is the only way to meaningfully lower property taxes in the long term.

This massive debt burden also drives Illinois’ worst-in-the-nation credit rating, leads to calls for tax hikes, crowds out spending on core government services and contributes to the state’s poor economic growth. Moreover, despite what many public employees have been led to believe, the poor financial condition of the state’s pension funds undermines government workers’ retirement security by placing the funds at risk of insolvency.30

While many state and local governments across the United States are struggling with pension debt – The Wall Street Journal reported the total of such debt at $4.2 trillion nationwide31 – Illinois’ pension crisis is the worst in the nation measured by ability to pay it off under the current benefit structure. For example:

- Moody’s found Illinois’ pension debt-to-revenue ratio reached an all-time high for any state in 2017 at 601%.32 After the record $5 billion income tax hike in 2017, Illinois still had the worst pension debt at 505% of revenues and nearly 28% of GDP, the highest in the nation.33 In personal finance, banks typically will not issue mortgage loans to anyone with a debt-to-income ratio of more than 43%.34

- Data from the National Association of State Retirement Administrators show that Illinois state and local governments already spend the most in the nation on pension benefits as a percentage of state and local revenues, nearly double the national average.35 This suggests increasing spending further – as state and local governments must do to keep up with payments, barring reform – is not the right solution to the debt problem.

- Michael Cembalest, chair of market and investment strategy at J.P. Morgan Asset and Wealth Management, found that while Illinois state government already spends more of its revenue on retirement benefits than any other state, it also has the largest gap between current contributions and the contributions that would be necessary to fully fund the system at existing benefit levels. Spending would need to nearly double from 26% of all Illinois state revenue to 51%.36

Simply put, tax hikes are not a viable solution to paying down Illinois’ pension debt.

According to Cembalest, going the tax hike route would mean Illinois needs to increase all tax revenues by 25% and dedicate all of it to retirement benefits.37 To put that in perspective, a tax hike of that magnitude would require a 50% increase in the state income tax, taking more than $1,800 from a median income family.38 If the economic harm of tax hikes were taken into account through a dynamic revenue estimate, tax hikes would need to be even higher to generate the funds required.

In a state already suffering from six straight years of population loss driven by high taxes, many residents would likely prefer to move elsewhere rather than stick around to pay exorbitant taxes that won’t give them any better government services.

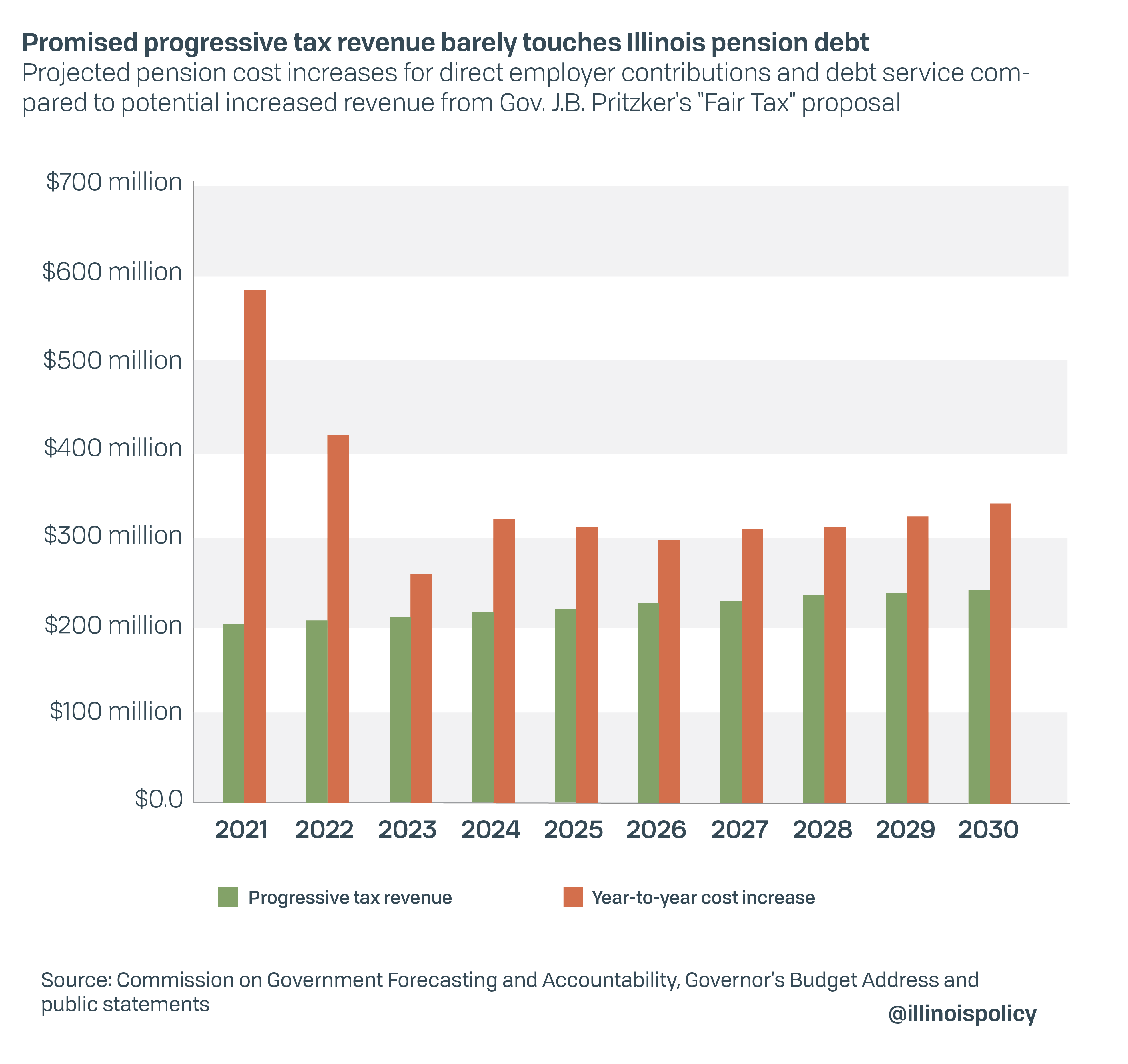

Likewise, Illinois cannot solve the problem by raising taxes only on higher-income earners through a progressive tax. Even if voters approved the progressive tax and then lawmakers dedicated all of the $3.4 billion tax hike to pensions, it would cover less than four months of annual pension spending.39 In reality, only $200 million of the new revenue has been tagged for higher pension contributions.40

This additional revenue is not enough to even keep Illinois level with annual pension cost increases, let alone meaningfully reduce unfunded liabilities. Illinois’ pension debt would continue to grow year after year under the current plan.

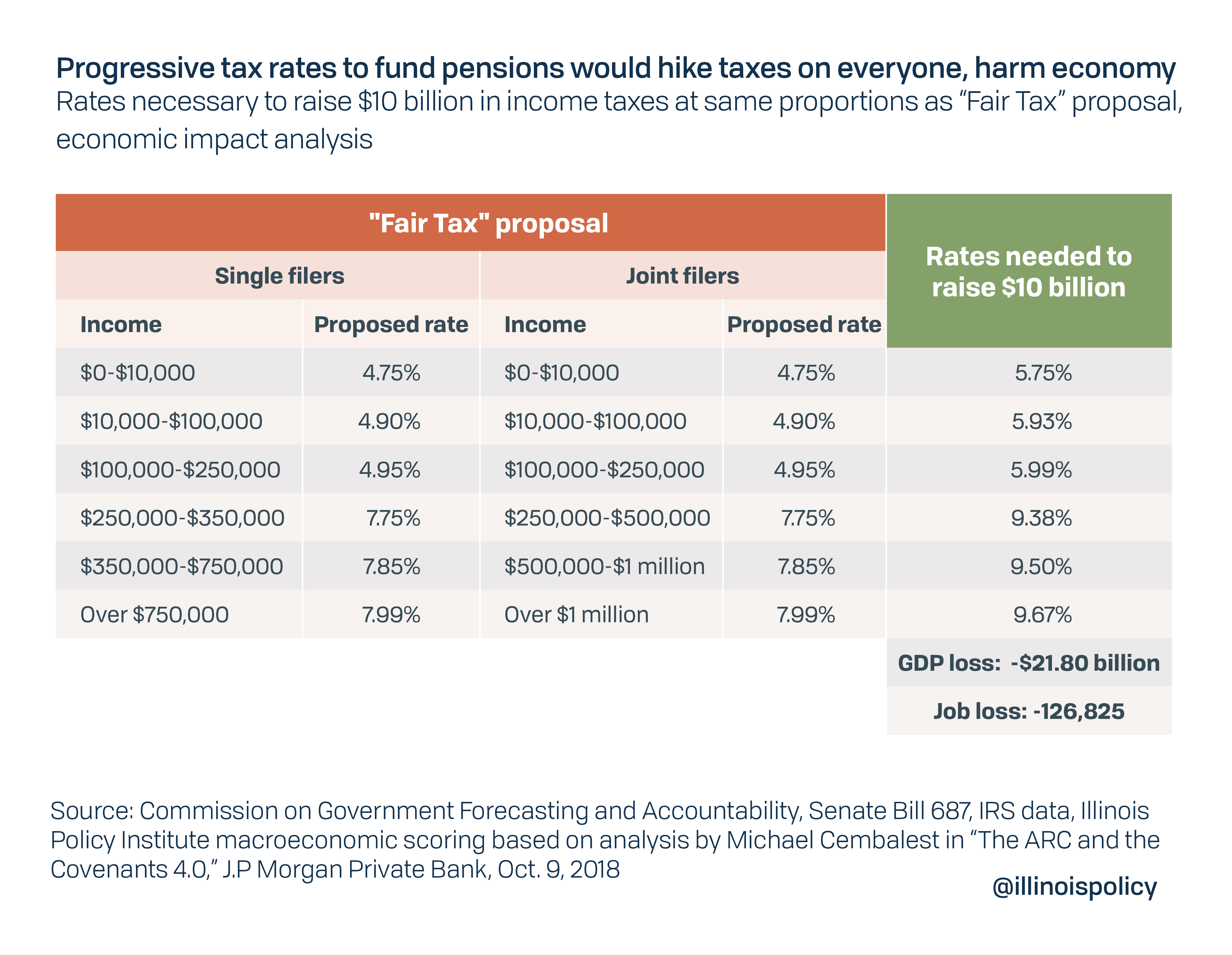

A progressive tax that would actually raise enough revenue to pay off the state’s unfunded pension liability would need to significantly raise taxes on everyone, rather than just the top 3% as has been promised. A tax hike of the size necessary to solve the problem could cost Illinois’ economy nearly 127,000 jobs and $21.8 billion in lost GDP.

The only other way out of Illinois’ pension crisis – and its negative effects on taxpayers, residents in need, the economy and government finances – is to reduce pension liabilities with benefit reforms. As shown below, benefit reforms can solve the pension problem while protecting both taxpayers and government workers. The biggest obstacle to a brighter future for Illinois has been and remains the lack of political will to pursue meaningful reform.

Public budgets tell us the priorities of our government. Right now, Illinois is prioritizing pensions over everything else.

Pension contributions accounted for less than 4% of Illinois’ general funds budget from 1990 through 1997.41 For fiscal year 2020, pension contributions and related costs will consume 25.5% of all general revenues at $10.2 billion.42 This figure includes:

- Direct contributions to the five state systems of $9.2 billion

- Debt service on pension obligation bonds worth $702.2 million

- The state’s contribution to Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund normal costs (the employer share of pension costs created by an additional year of work) of $257.4 million

- $47 million in new debt service costs for pension buyout bonds

The rapidly increasing cost of pensions is crowding out spending for core government services. As noted earlier, growth in pension spending has far exceeded other budget categories, while spending on programs and services has actually declined as dollars have drained into pensions.

Some of the programs that have suffered from pension crowd-out include the state police, helping poor students pay for college, protecting children from child abuse, aiding the poor, fighting disease and other public health issues, and much more.43

In 2013, a Democratic supermajority-controlled Illinois General Assembly passed a reform package that would have preserved retirees’ earned benefits while modifying future growth rates in liabilities to make them affordable. Public Act 98-0599 would have saved the state more than $1 billion per year in annual pension contributions and eliminated nearly $24 billion of the state’s pension debt.44

Unfortunately, the Illinois Supreme Court struck down those modest reforms in their entirety, ruling in 2015 that the pension clause of the state constitution guarantees as of the day an employee is hired the entire benefit formula both for work already performed and for benefits that have not yet been accrued.45 In other words, the court left the state no flexibility whatsoever to change benefits for existing workers and retirees whose benefits are the core of the pension crisis.

Prior to the 2013 reforms, the state implemented a less generous benefit schedule for employees hired in 2011 or later.46 Tier 2 pensioners have more reasonable retirement ages, higher employee contributions, a cap on maximum pensionable salary and a true cost-of-living adjustment, or COLA, indexed to inflation.47 Tier 1 retirees in the state systems receive a guaranteed 3% compounding annual raise after retirement. This should not be called a “COLA” because it has no relation to how inflation changes the actual cost of living.

Illinois pension debt exists almost entirely because of benefits for Tier 1 workers and retirees, those who began working for an eligible government employer prior to 2011. In fact, younger workers in Tier 2 may actually be subsidizing Tier 1 benefits by paying in more than they’ll receive, at least for teachers.48 As a result, teacher advocacy groups have predicted if the state does not alter Tier 2 benefits, a lawsuit against the state is likely.49 A lawsuit could force higher benefits and increase the state’s pension debt even further.

Thankfully, other states have shown Illinois the way forward. After their state’s highest court blocked statutory pension reform, Arizona voters approved two amendments to their state constitution that enabled them to reform pension benefits, including by lowering COLAs.50

Illinois must follow that lead, both to fix its long-term structural deficit and to make the pension system sustainable for retirees.

Constitutional amendment: Protecting earned benefits, reforming future growth

Residents across the state deserve the opportunity to vote on an amendment to the state constitution that would enable commonsense pension reform.

An amendment to recognize the distinction between past and future benefits has begun to gain traction in the state after being promoted by the Illinois Policy Institute last year. State Rep. Deanne Mazzochi, R-Elmhurst, introduced a constitutional amendment in 2020 that can protect earned benefits while giving the state flexibility to modify future accruals.51 In broad terms, the idea has been endorsed by former Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel,52 the Chicago Tribune editorial board53 and received positive coverage from the Chicago Sun-Times.54

Lawmakers should immediately act on Mazzochi’s amendment and allow Illinoisans to vote on it in November 2020, the same time they will be asked to vote on the progressive income tax amendment. The longer the pension system is left to limp along without reform, the harder it becomes to save the system without severe cuts to benefits.

However, if lawmakers were to pass pension reform legislation to accompany the amendment – which would take effect upon the amendment receiving voter approval – they could re-work the state’s pension funding ramp so savings could be realized immediately, starting with fiscal year 2021.

Using the bipartisan 2013 reforms as an example, lawmakers should pursue the following:

- Increase the funding target to 100% from 90% in accordance with actuarial best practices. The goal year for 100% funding would remain 2045.

- Gradually increase retirement ages for current workers under age 45 by a maximum of five years.

- Apply a pensionable salary cap of $100,000 that grows with inflation. Government workers could still earn more than $100,000, but their pensions could not be based on more than the cap. The cap would only apply to employees not currently receiving a retirement check.

- Replace Tier 1 retirees’ 3% compounding benefit increase with true cost-of-living adjustments tied to inflation. Annual increases would be simple, not compounding, and rise with CPI-U as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- Increase Tier 2 COLAs from half of inflation to full inflation. This would end the unfair subsidization of older workers by younger workers and could prevent a potential lawsuit.

- Implement COLA holidays to allow inflation to catch up to past benefit increases. If a worker has been retired for eight years or more, they would skip every other year for 16 years for a total of eight adjustment periods at 0%. If a retiree has been receiving benefits for seven years, they would skip one payment every other year for 14 years, and so on.

- Enroll all newly hired employees in a defined contribution personal retirement account with a 4% guaranteed employer match. This would ensure the state never gets into pension trouble again, as defined contribution systems are inherently less risky and more predictable. This would also provide state workers with a portable retirement benefit they could take with them from employer to employer, rather than being forced to stay with the state in order to maximize retirement benefits.

Remember that benefit changes would apply to existing workers and retirees, but only to future benefits.

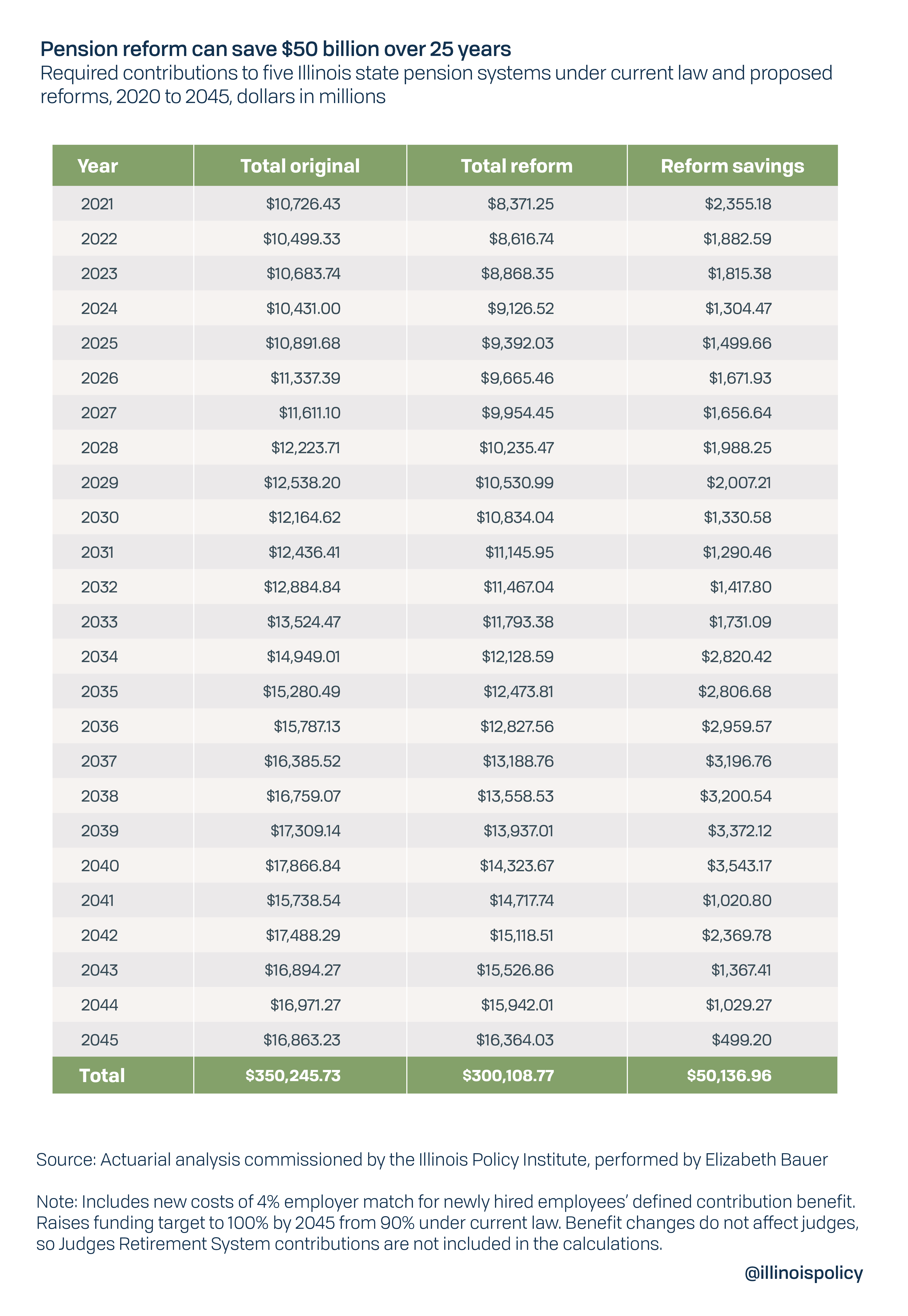

An original actuarial analysis commissioned by the Illinois Policy Institute shows how far these modest reforms can go to bring Illinois back from the brink. The analysis was performed by Elizabeth Bauer, a certified actuary who frequently writes about pension policy for “Forbes” magazine. Bauer’s analysis showed that in the first year, this reform package would save nearly $2.4 billion for the state budget. From now until 2045, these reforms would save the state more than $50 billion in taxpayer contributions.

These savings are achievable even though the state would be subjecting itself to stricter funding requirements while simultaneously adding a new expense in the form of a defined contribution system for new employees. This shows just how powerful even modest pension changes can be.

To understand why future benefit reform works, it’s necessary to understand how pension debt differs from other forms of government debt.

Pension liabilities are not the same as bonds, where a set amount has been borrowed and has to be repaid. They are a future value calculation based on assumptions about the growth in benefits for workers and retirees. Overnight, the state’s total pension liability of $223.3 billion would drop by $25.5 billion with the reform package outlined because benefits would grow slower in the future. In turn, this reduces the amount the state must pay annually to reach full funding.

These savings are also achievable while preserving the core benefit for every worker and retiree. No retired person would see the size of their current check decrease and no current worker would see their currently promised monthly annuity shrink.

There is no fairer solution for both taxpayers and those relying on Illinois’ pension systems for their retirement security.

Aligning responsibility for payment with accountability for benefits

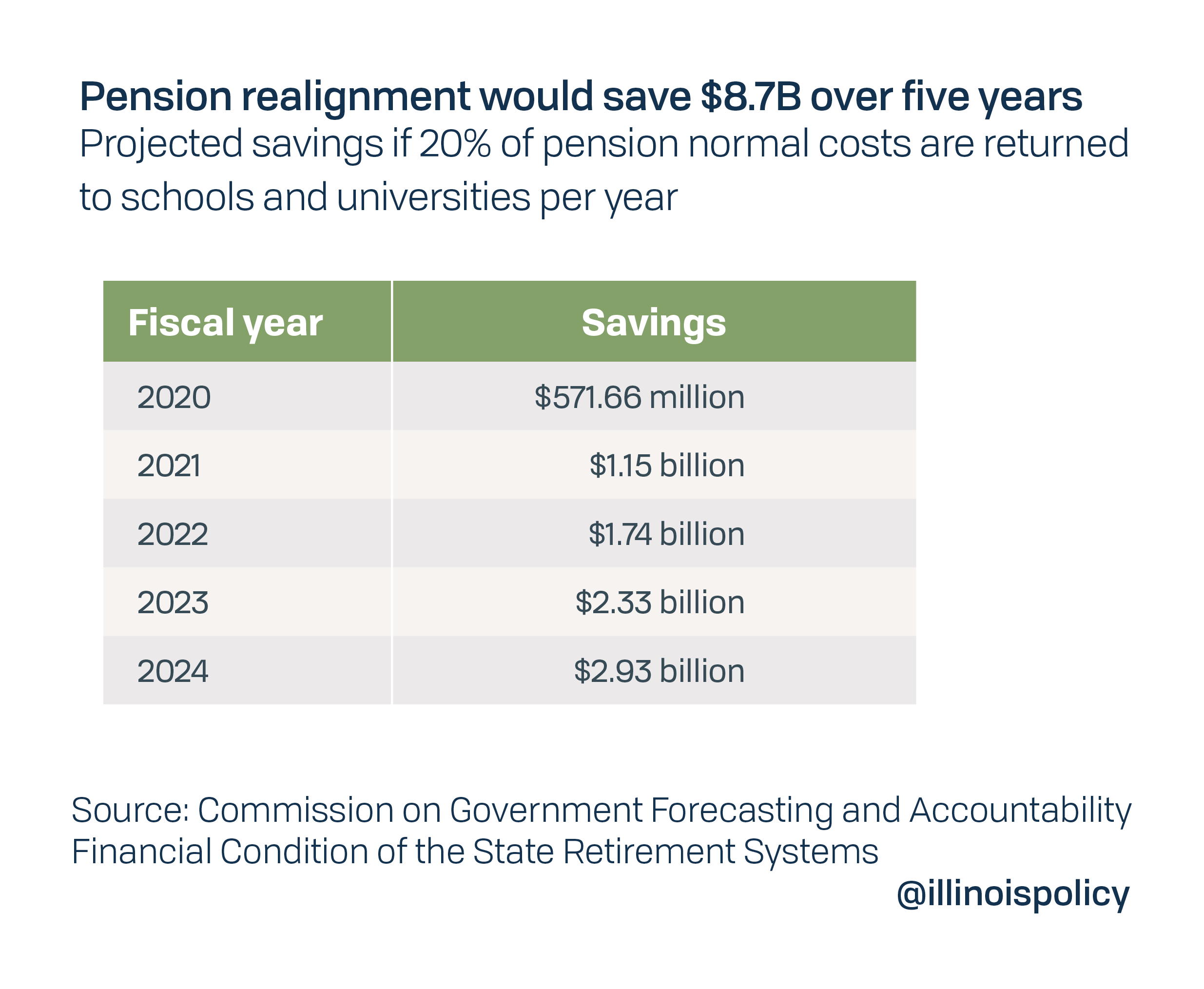

A second way Illinois can see immediate pension savings would be to realign the cost of paying for “normal costs” – the pension cost of an additional year of work – so that the one responsible for setting benefit levels is accountable for paying the bill.

Currently K-12 and state university administrators negotiate salary and health benefits, which form the basis for pension payments and retiree health costs, but the state pays the employer contributions. That creates a misalignment between responsibility and accountability, reducing pressure to keep compensation affordable for taxpayers.

In other words, realigning future pension costs for schools and universities would both save money for the state and encourage administrators to control the costs of pensions in the long run through more responsible collective bargaining.

Both political parties have supported pension realignment over the years.

Former Gov. Bruce Rauner, a Republican, proposed this idea in each of his budget addresses from 2014-2018.55 Speaker of the Illinois House of Representatives Michael Madigan, a Democrat, also supported the idea in 2012,56 and said the change was “inevitable” as recently as 2013.57

If gradually phased in over five years to allow schools and universities time to adjust, pension realignment savings would be nearly $572 million in the first year and rise to nearly $3 billion by the fifth year.

On average, realigning responsibility to pay for pension normal costs would only increase each district’s payroll costs by about 2.5% per year.58 The state would remain responsible for making payments on the unfunded portion of the pension liability so schools would be paying only the new annual cost of pensions. Those new annual costs would also be lower if the state pursued constitutional pension reform, meaning that schools wouldn’t even necessarily absorb normal costs of the same size as state savings.

Together, these factors mean schools should be able to pay for these normal costs without seeking to raise new revenue from property taxes. However, while the impact to each district would be relatively small, districts would need to make some changes in their own budgets to accommodate the new costs.

One opportunity for budget savings for many school districts would be ending the practice of “pension pick-ups,” in which the employer pays some or all of what is supposed to be the employee’s contribution to their own pension. As of the most recent teacher salary survey conducted by the Illinois State Board of Education, 60% of school districts pick up at least a portion of the employee contribution, and 38% cover the entire portion teachers are by law supposed to contribute.59

For example, Chicago Public Schools currently picks up 7 percentage points of the 9% employee contribution. As a result, the average teacher recoups every penny they paid into the pension system within less than five months of retirement.60

Additionally, the state can assist local school districts by helping to consolidate unnecessary layers of administration to find savings.

Empowering students to achieve their full potential with efficient school district administration

The goal of public education should be to ensure that every student has the opportunity to maximize his or her full potential. Unfortunately, the Prairie State currently falls short of this goal because of a top-heavy education bureaucracy diverting resources that should rightly be going to classrooms for teachers and students.

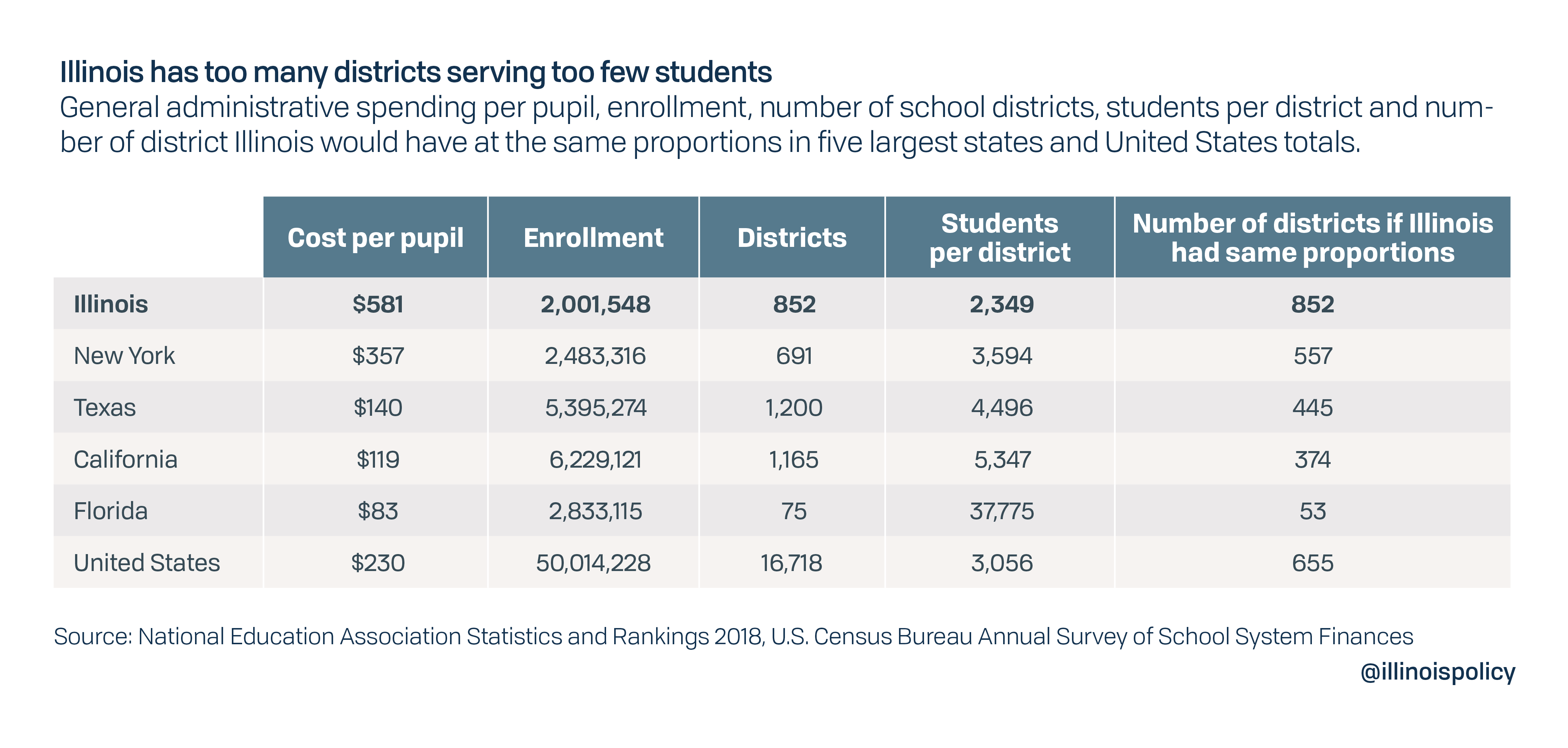

Illinois is the only state that spent more than $1 billion on district-level administrative costs in 2017, the most recent year of data available from the U.S. Census Bureau.61 California has three times as many students, but spent nearly 40% less than Illinois on district administration. This spending only represents costs of the superintendent and school board. It does not include administrative spending within the school, such as on guidance counselors or principals.

Illinois spends $581 per student on district-level administration, more than double the national average of $230.62 If Illinois reduced its general administrative spending to the national average per student, it would save $708 million on unnecessary costs that could be reinvested in the classroom to improve student outcomes or returned to overburdened property taxpayers.

Illinois must consolidate school districts to reduce unnecessary administrative spending. Each district comes with highly paid superintendents, support staff and costly facilities. If districts serve more schools and more students, they can achieve economies of scale and greater efficiency without losing services.

Importantly, consolidation of school districts involves merging administrative bodies, not closing individual schools.

In spring 2019, the Classrooms First Act – House Bill 3053, introduced by state Rep. Rita Mayfield, D-Waukegan – unanimously passed the Illinois House of Representatives in a bipartisan 109-0 vote.63 The bill would create the School District Efficiency Commission, tasked with making recommendations for consolidating districts, with the goal of at least a 25% reduction in bureaucracy.

The commission’s recommendations would go directly to voters as a ballot question, putting control in the hands of parents, teachers and local taxpayers living within the school district. Voters in each affected school district would have to approve the consolidation by a majority vote, so one district could not force another to merge unless residents in each separately agreed. The bill does not contain any mandates or one-size-fits-all solutions: local residents would be in control of determining what is right for their community.

While the bill stalled in a Senate committee last spring, it will be taken up again in the spring 2020 legislative session. If lawmakers pass the Classrooms First Act, more resources for schools can make it to students and teachers, rather than being eaten up by wasteful bureaucracy.

Academic research has consistently found more efficient school districts improve educational outcomes for students.64 A 2018 study found that increasing the size of a district to 1,000 students improves the average SAT score by 48 points; increasing the size again to 2,000 students can increase the average SAT score by an additional 15 points.65

Putting more money into classrooms through consolidation of school districts can ease pressure on the state budget and allow state aid to local districts to grow more slowly than planned under current law without negatively affecting education outcomes.

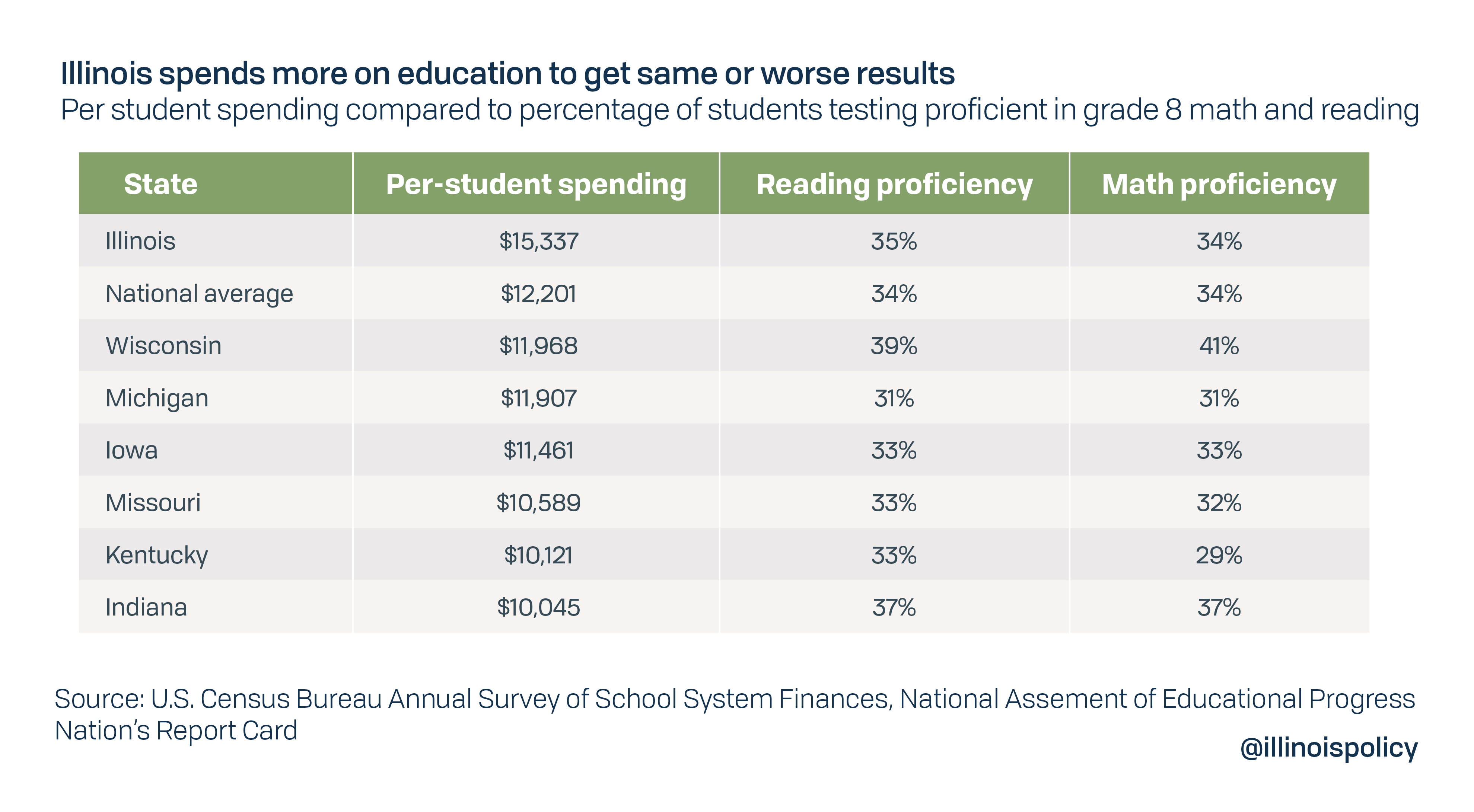

Illinois’ current school funding formula sets a target of increasing total K-12 education spending by $350 million per year.66 This target is arbitrary and not based on best practices for education funding. Data do not support the idea that pouring more taxpayer dollars into the current system, without reform, is the right way to maximize student potential.

Several of Illinois’ neighboring states spend less per student and get better results. For example, Wisconsin, Iowa and Indiana spend between $3,369 and $5,332 less per student than Illinois, but all three states have better proficiency scores on the Nation’s Report Card for both reading and math.

Instead of arbitrary annual increases, Illinois should grow state aid for K-12 schools at the expected rate of inflation, or roughly 2% per year. If combined with more efficient school districts and fewer resources lost to administrative waste, this strategy should improve student outcomes by spending the money smarter, rather than just spending more.

Compared to baseline budget projections, this smart spending strategy would save nearly $290 million in Year 1 and nearly $3.6 billion in five years.

Fixing the broken budget process to end business as usual

Elected leaders in Illinois created the state’s fiscal crisis by consistently spending more than they collected in revenue and using unrealistic budget projections. However, the broken budget process in the state has enabled and even encouraged much of this behavior.67

Currently, bad budget rules in the Illinois Constitution and state law place too few constraints on Springfield lawmakers’ spending habits. A broad body of academic literature has found that formal budget rules and procedures, or lack thereof, are an important contributor to restraining politicians’ worst impulses and ensuring good budget outcomes.68

To ensure that future Illinois elected leaders deliver better budgets, taxpayers should push the General Assembly to adopt a spending cap and fix the currently ineffective balanced budget requirement.

Spending and revenue caps can be found in some form in 27 U.S. states,69 but not Illinois. These rules prevent government spending from growing faster than a measure of economic growth, such as GDP or personal income. The goal is to make sure politicians cannot spend more than the taxpayers who fund government can afford.

A spending cap is sorely needed in Illinois. Research from the Institute of Government Affairs at the University of Illinois shows that from 1998 to 2018 revenues grew in real terms by 47%, but were outpaced by a 57% increase in spending.70

Additionally, lawmakers should strengthen the state’s balanced budget requirement.

While Illinois already technically requires a balanced budget, the law is toothless. The state constitution reads: “The General Assembly by law shall make appropriations for all expenditures of public funds by the State. Appropriations for a fiscal year shall not exceed funds estimated by the General Assembly to be available during that year.”71

The problem is that revenue projections can easily be inflated so that “estimated” funds are significantly higher than actual collections. The Illinois Constitution does not create a requirement to match actual expenditures and actual revenues at the end of a fiscal year. That makes Illinois one of just 11 states that permit a deficit to be carried from one year to the next, according to the most recent survey of the National Association of State Budget Officers.72

The other 39 states have true balanced budget requirements.

While taxpayers would be best served by enshrining a spending cap and true balanced budget requirement in the Illinois Constitution, so they could not easily be overridden by any given General Assembly, a good start would be to at least put these rules in state statutes.

Only with better budget rules can taxpayers be assured Springfield will responsibly spend their money.

Conclusion: Advancing Illinois means embracing bipartisan policy solutions, rejecting further tax hikes

Tax hikes have consistently failed to fix Illinois’ ailing finances. In a high-tax state such as Illinois, trying to balance budgets and pay off debt with nothing but higher revenues is a self-defeating strategy that drives away residents and businesses, harming the economy.

The proposed progressive income tax amendment facing voters in November is far from the best or only option to correct the state’s finances. It would constitute the most harmful policy response yet to Illinois’ major fiscal and demographic problems.

Illinois’ biggest problem, pension debt, cannot be eliminated without structural benefit reform to shrink the size of the liabilities, or the future promises made to workers. This is true regardless of whether Illinois voters approve a progressive income tax amendment. And it has caused some experts, including Michael Cembalest from J.P. Morgan, to support asking the federal government to allow state-level bankruptcy similar to what happened in the U.S territory of Puerto Rico.73

Fortunately, Illinois can still be brought back from the brink if elected leaders get serious about bipartisan spending reforms that have seen success in other states. The three commonsense proposals in this report show how.

Illinoisans deserve a state government that respects their wallets and provides them with valuable services. Unsustainable pension costs and ever-rising tax burdens deprive them of both.

Endnotes

- Adam Schuster, “Budget Solutions 2020: A 5-year plan to balance Illinois’ budget, pay off debt and cut taxes,” Illinois Policy Institute, February 2019.

- Adam Schuster, “Pritzker’s AFSCME Deal Gives 12% Automatic Raises, $2,500 Bonus to State Workers,” Illinois Policy Institute, June 26, 2019.

- Truth in Accounting, “Financial State of the States,” September 2019.

- Ibid.

- Eileen Norcross and Olivia Gonzales, “Ranking the States by Fiscal Condition: 2018 Edition,” Mercatus Research Paper, Oct. 9, 2018.

- Ben Szalinski, “No. 2 New Jersey Confronts Pension Crisis as No. 1 Illinois Dithers,” Illinois Policy Institute, June 12, 2019.

- Adam Schuster, “Illinois Income Tax Hikes Failed to Fix State Finances,” Illinois Policy Institute, Sept. 2, 2019.

- Orphe Divounguy and Bryce Hill, “Illinois Saw Nation’s Worst Population Loss During the Decade,” Illinois Policy Institute, Dec. 30, 2019.

- Center for State Policy and Leadership, University of Illinois-Springfield, and NPR Illinois, “The 2018 Illinois Issues Survey,” Sept. 26, 2018.

- See: Richard J. Cebula, 2009, “Migration and the Tiebout-Tullock Hypothesis Revisited,” The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 68(2): 541-552; Mark Gius, 2011 “The Effects of Income Taxes on Interstate Migration: An Analysis by Age and Race,” The Annals of Regional Science, 46(1): 205-218; Andrew Lai, Roger Cohen, and Charles Steindel, “The Effects of Maginal Tax Rates on Interstate Migration in the U.S.”, New Jersey Department of the Treasury, October 2011; Richard J. Cebula and Usha Nair-Reichert, “Migration and Public Policies: A Further Empirical Analysis,” Journal of Economics and Finance, 36(1): 238-248; Roger Cohen, Andrew Lai, and Charles Steindel, “State Income Taxes and Interstate Migration,” Business Economics, 49(3):176-190; Antony Davies and John Pulito, “Tax Rates and Migration,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, August 2011; Richard Cebula, Usha Nair-Reichert, and Christopher Coombs, 2014, “Total State In-Migration Rates and Public Policy In the United States: A Comparative Analysis Of the Great Recession and the Pre- and Post-Great Recession Years,” Regional Studies, Regional Science, (1): 102-115.

- Jacob M. Feldman, 2012 “State Income Migration and Border Tax Burdens,” Americans for Tax Reform, March 2012; Chris Edwards, “Tax Reform and Interstate Migration,” Cato Institute, Sept. 6, 2018.

- Chris Edwards, “Tax Reform and Interstate Migration,” Cato Institute, Sept. 6, 2018.

- Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill, and Joe Tabor, “Why the 2017 Tax Hikes Will Harm Illinois’ Economy,” Illinois Policy Institute, Winter 2018.

- Rocky Mengle and David Muhlbaum, “The 10 Least Tax-Friendly States in the U.S.”, Kliplinger, Oct. 1, 2019.

- See for example: Tax Foundation, “State-Local Tax Burden Rankings FY 2012,” January 20, 2016.

- Adam Schuster, “Pritzker Signs Illinois Budget Out of Balance by Up to $1.3 Billion,” Illinois Policy Institute, June 11, 2019.

- Adam Schuster, “20 Tax and Fee Hikes Totaling $4.6 Billion Coming Soon for Illinoisans,” Illinois Policy Institute, June 14, 2019.

- Orphe Divounguy, Adam Schuster, and Bryce Hill, “Progressive Income Tax Study Guide,” Illinois Policy Institute, Dec. 10, 2019.

- State of Illinois, “Illinois Economic and Fiscal Policy Report,” Oct. 23, 2019: p. 11.

- Adam Schuster, “False Choice for Illinois: Pritzker’s Budget Ignores Common Sense Alternative,” Illinois Policy Institute, March 12, 2019.

- Jared Walczak, “Tax Trends at the Dawn of 2020,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 6, 2020.

- Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, “Financial Condition of Illinois State Retirement Systems as of June 30, 2018,” April 2019: p. i.

- Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, “A Report on the Financial Condition of the Illinois Municipal, Chicago and Cook County Pension Funds of Illinois,” January 2019, p. iii.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “The State Pension Funding Gap: 2017,” June 27, 2019.

- Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, “A Report on the Financial Condition of the Illinois Municipal, Chicago and Cook County Pension Funds of Illinois,” January 2019, p. 30 & 42.

- Ibid, p. 68.

- Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, “Report on the Financial Condition of the Downstate Police and Downstate Fire Pension Funds,” July 2019.

- See for example: Moody’s Investors Services, “US States’ Pension Liabilities Fall in Fiscal 2018 Amid Higher Investment Returns,” Sept. 17, 2019; Michael Cembalest, “The ARC and the Covenants 4.0,” J.P. Morgan Private Bank, Oct. 9, 2018.

- Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill, and Joe Tabor, “Pensions Make Illinois Property Taxes Among Nation’s Most Painful,” Illinois Policy Institute, Summer 2018.

- Adam Schuster, “Illinois Public Services Being Cut to Pay Unsustainable Pension Costs,” Illinois Policy Institute, Fall 2019.

- Heather Gillers, “America’s Pension Funds Fell Short in 2019,” The Wall Street Journal, Aug. 6, 2019.

- Moody’s Investors Services, “Unfunded US State Pension Liabilities Surge in Fiscal 2017 Due to Poor Investment Returns,” Aug. 27, 2018.

- Moody’s Investors Services, “US States’ Pension Liabilities Fall in Fiscal 2018 Amid Higher Investment Returns,” Sept. 17, 2019.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “What is a Debt-to-Income Ratio? Why is the 43% Debt-to-Income Ratio Important?” Updated Nov. 15, 2019.

- Adam Schuster, “Illinois State and Local Governments Spend Most in Nation on Pensions,” Illinois Policy Institute, Feb. 22, 2019.

- Michael Cembalest, “The ARC and the Covenants 4.0,” J.P. Morgan Private Bank, Oct. 9, 2018.

- Ibid, p. 2.

- Illinois Policy Institute calculations. Median family is married with two kids, makes $79,168, pays $3,712 in state income taxes annually. A 25% increase in revenues would be $10 billion for fiscal year 2020, 50.9% of the $19.7 billion net individual tax collections projected by the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability for the year.

- Austin Berg and Adam Schuster, “Pritzker’s $3.4B Income Tax Hike Can Fund Less than 4 Months of State Pension Costs,” Illinois Policy Institute, March 31, 2019.

- Tivas Gupta and Adam Schuster, “Pritzker Promises Over $10B in New Spending on $3.4B Progressive Tax Hike,” Illinois Policy Institute, Aug. 7, 2019.

- Adam Schuster, “Tax Hikes vs. Reform: Why Illinois Must Amend Its Constitution to Fix the Pension Crisis,”Illinois Policy Institute, Summer 2018.

- Official reporting understates taxpayer spending on the pension system by breaking pension spending into multiple categories, the names of which do not clearly indicate the money is going towards the state pension system. The Illinois Policy Institute adjusts the official numbers by adding Pension Obligation Bond debt service, pension buyout debt service, and Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund normal costs back into pension spending. “Other state funds” pension contributions from unclaimed property sales are not included in GOMB reporting of General Revenue Fund dollars, but are added back to Institute analyses, to both revenues and expenditures, to give a full accounting of pension costs to taxpayers and the state budget.

- Adam Schuster, “Illinois Services Being Cut to Pay Unsustainable Pension Costs,” Illinois Policy Institute, Fall 2019.

- Adam Schuster, “Tax Hikes vs. Reform.”

- In re Pension Reform Litigation, IL 118585 (2015).

- Illinois Public Act 96-0889.

- 40 ILCS 5/15-108.2.

- Elizabeth Bauer, “More Cautionary Tales From Illinois: Tier II Pensions (And Why Actuaries Matter),” Forbes, June 7, 2019.

- Dusty Rhodes interview with Jessica Handy, “Ed Advocacy Group Tries to Make Shift Happen,” NPR Illinois, June 13, 2019.

- Adam Schuster, “Arizona Voters Show Illinois the Path Forward on Pensions,” Illinois Policy Institute, Nov. 19, 2018.

- Illinois General Assembly, House Joint Resolution Constitutional Amendment 38.

- Adam Schuster, “Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel Endorses Pension Amendment to Illinois Constitution,” Dec. 11, 2018.

- Editorial Board, “The Quest for a Pension Amendment: Can Pritzker and Lightfoot Save Illinois from Itself?”Chicago Tribune, June 5, 2019.

- Editorial Board, “Beware of the Disinformation Campaign Against A Fairer Tax for Illinois,” Chicago Sun-Times, Aug. 9, 2019.

- Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, “Proposed Operating Budget,” Fiscal Years 2016 through 2019.

- Greg Bishop, “Lawmakers Debate Governor’s Pension Cost Shift Proposal,” Illinois News Network, May 10, 2018.

- Doug T. Graham, “Madigan: Putting Pension Costs on Schools ‘Going to Happen’,” Daily Herald, May 10, 2013.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, “Illinois’ Regressive Pension Funding Scheme: Wealthiest School Districts Benefit Most,” Wirepoints, March 9, 2018.

- Illinois Policy Institute calculations based on Illinois State Board of Education 2018-2019 Teacher Salary Study.

- Adam Schuster, “Chicago Teachers Recover Pension Contributions 5 Months Into Retirement,” Illinois Policy Institute, Oct. 29, 2019.

- U.S. Census Bureau, 2017 Annual Survey of School System Finances.

- Ibid.

- ILGA.gov, 101st General Assembly, vote history for House Bill 3053.

- Orphe Divounguy, Adam Schuster, and Bryce Hill, “Bureaucrats Over Classrooms: Illinois Wastes Millions of Education Dollars on Unnecessary Layers of Administration,” Illinois Policy Institute, Summer 2019.

- Srikant Devaraj, Dagney Faulk, and Michael Hicks, “School District Size and Student Performance,” Journal of Regional Analysis & Policy 48.4 (2018): 25-37, Nov. 9, 2018.

- Public Act 100-0465.

- Adam Schuster, “Bad Budgeting Basics: How Illinois’ Budget Process Hurts Taxpayers,” Illinois Policy Institute, Spring 2018.

- See, e.g., Henning Bohn and Robert P. Inman, “Balanced-Budget Rules and Public Deficits: Evidence from the U.S. States,” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 45 (December 1996): 13-76; Gary A. Wagner and Erick M. Elder, “The Role of Budget Stabilization Funds in Smoothing Government Expenditures over the Business Cycle,” Public Finance Review, 33(4) (July 1, 2005); Antonio Fatás and Ilian Mihov, “The Macroeconomic Effects Of Fiscal Rules In the US States,” Journal of Public Economics, 90 (1-2) (May 2004): 101-117; Fred Thompson and Bruce Gates, “Betting on the Future with a Cloudy Crystal Ball: Revenue Forecasting, Financial Theory, and Budgets – An Expanded Treatment,” Public Administration Review, 67(5), September/October 2007; Leslie McGranahan and Richard Mattoon, “Revenue Cyclicality and Changes in Income and Policy,” Public Budgeting and Finance 32(4), December 2012, 95-119; Donald J. Boyd and Lucy Dadayan, “State Tax Revenue Forecasting Accuracy,” Rockefeller Institute of Government, September 2014.

- National Association of State Budget Officers, “Budget Processes in the States,” Spring 2015.

- Lauren Silva Laughlin, “Illinois Budget Woes: Still Smoking,” The Wall Street Journal, June 11, 2019.

- Ill. Const. art. VIII, § 2(b).

- National Association of State Budget Officers, “Budget Processes in the States,” Spring 2015.

- Michael Cembalest, “The ARC and the Covenants 4.0, the State of the States 2018,” Eye on the Market, Special Edition, Oct. 9, 2018.